At the Veterinary Dental Center of Atlanta, our experienced team is skilled in diagnosing and treating periodontal disease and vestibular bone expansion in cats. Unfortunately, in many instances, the expansion can be too extreme to treat and extraction becomes necessary. However, prompt detection and treatment can avoid this outcome. Here, we will show how prompt intervention can conserve your cat’s teeth and enhance their overall dental well-being.

Periodontal disease and vestibular bone expansion in cats is common. Many times the expansion in cats is too severe to treat and extraction is necessary. Here we demonstrate a case where expansion is early and treatment is indicated.

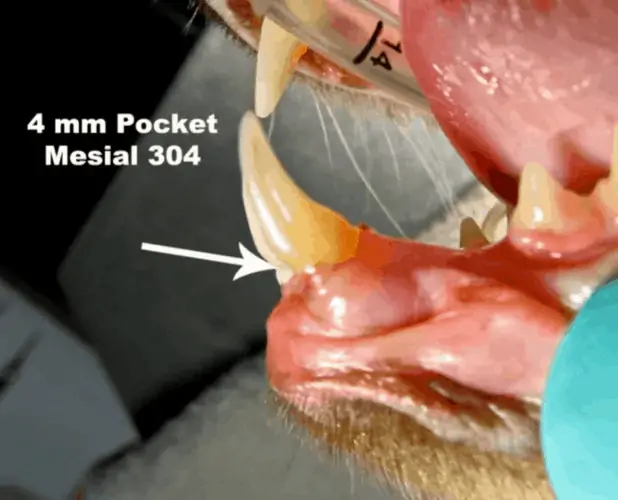

We probably don’t have a lot of cases where we can actually treat cats with periodontal disease with anything other than extraction but this is an exception. In a situation where we’ve got bone expansion that is not severe with good skills in surgical extractions you will eventually be able to comfortably do this. You guys are doing really well and you’ve developed a lot of skills over the last day and a half (at the Canine and Feline Extraction Wet Lab). You’ll be able to take those same skills in the flap creation and do what I’m about to show you here if you have an indication for it. This is not real common but, it occurs enough where you’re going to see it. This will be something that you can use. This patient has minimal gross change on the left side shown above. There’s the pocketing there. If we took a periodontal probe and went down in, we’d have a 3-4 millimeter pocket there. You can see there’s a little bit of extrusion where we’ve got the neck of the tooth here and the gingival margins here.

As you can see the right side here of the same patient is more severe.

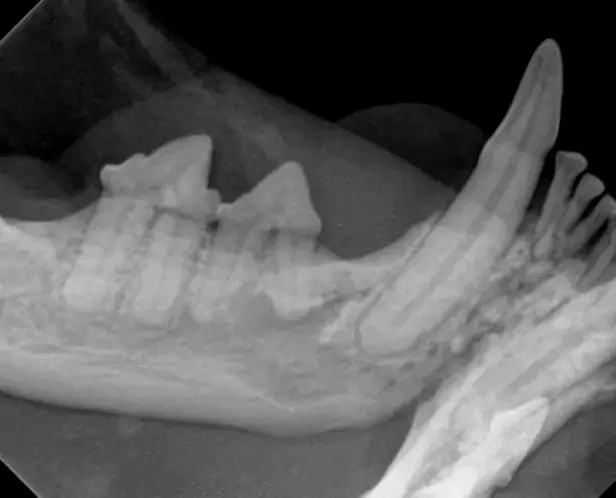

Here you can see radiographically vestibular bone expansion but instead of being in the maxilla like it is normally, it’s in the mandible. (same tooth as the above image) In periodontal disease, one of the common things we look for which is an increased periodontal ligament space. You can see on that surrounding the tooth root there’s a huge periodontal ligament space. That’s too severe. That’s an extraction, there’s no doubt about that.

On the other hand, we do have some patients that have it when it first starts happening and this is one of those. If you look there on that mesial aspect and a little bit on this side, on the distal aspect first and then the mesial aspect by the incisor. You’ve got a little bit of pulling away of that bone from where it should be, adjacent to that tooth. If you find vestibular bone expansion at that level, a lot of times we can treat those.

When you look at it this view you can see it’s more significant.

Our goal is to recreate that bone margin and reposition the gingiva more apical on the new bone level we’ve got a chance to to save that tooth with a fairly simple procedure. If you don’t know surgical extractions and you’re not good at extracting that mandibular canine tooth, you wouldn’t want to think about doing this procedure but, if you’re reasonably good and comfortable at surgical extractions, you can definitely do this.

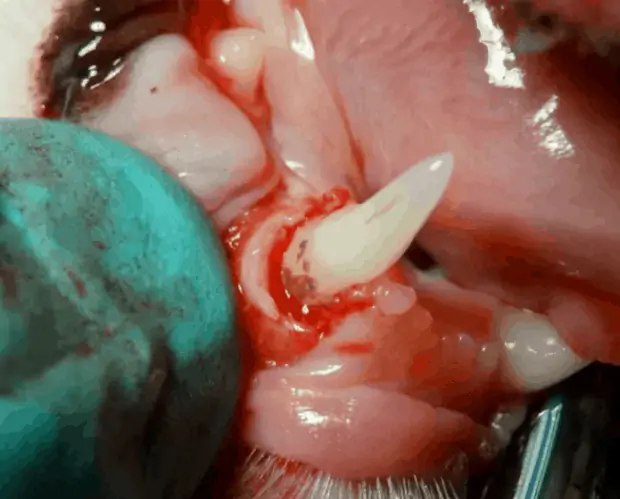

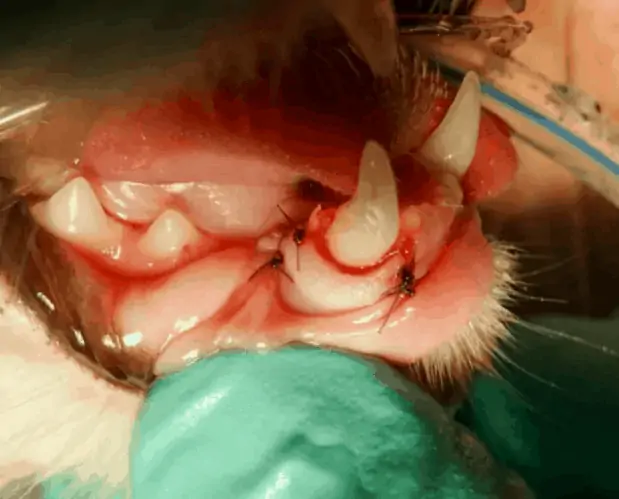

This is what it looks like upon exposure. All that dark material that’s down in there, that’s either necrotic cementum, calculus, or some other debris. Root planing and subgingival curretage with a periodontal curette will remove effectively remove the debris. We can also use our ultrasonic scaler, clean that off, make it nice and smooth, polish it. Then we’re left with that ridge of bone that we want to take down and eliminate that cup-like defect with a fine diamond bur.

Here we want to eliminate the vertical component to the base of that vertical defect by contouring the bone from coronal to apical, just like it would be normally.

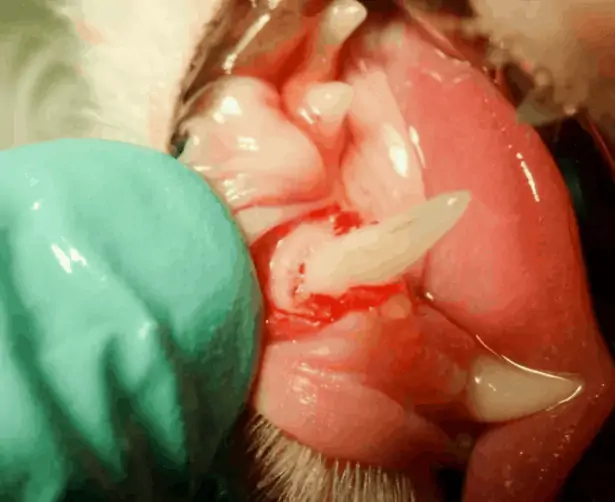

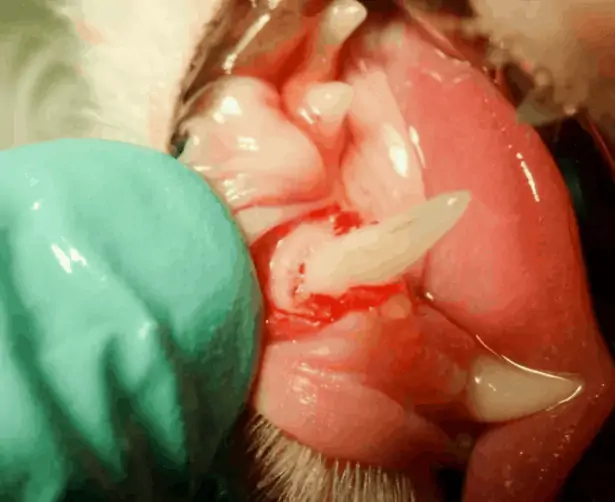

There it’s cleaned up and now we’ve got that bone where it’s contoured. It’s not straight across, it’s contoured down or apical so that it recreates what normally would be there if the bone was at a normal bone level.

There it’s cleaned up and now we’ve got that bone where it’s contoured. It’s not straight across, it’s contoured down or apical so that it recreates what normally would be there if the bone was at a normal bone level.

Once that’s all cleaned up and the bone is contoured, then we suture the gingiva down below that normal level. It’s not up against the neck of the tooth where it’s supposed to be, it’s down on the bone level. What we’re doing there is we’re recreating the biological width. We’re allowing for the normal pocket and attachment interface between the gum in the bone and the tooth to be recreated so that that can reattach and be normal again once that heals. Looking at it from that view, that’s immediately post-op.

There’s a view of it before…

…and after. You can’t really tell it that much there but, on the other view you can definitely tell it.

There’s before…

…and there’s after. We extracted those two incisors that were adjacent to those canines because they had enough bone loss to extract.

Here is the 3 month post surgery view. We managed to save that canine tooth short term but the owner is going to have to come back periodically and get that evaluated. This is a 4 year old cat so it will need to be on a regimen that is specific for him to prevent progression from here. We don’t want return of gingivitis pocketing. In general this interval in between 4 months, 10 months.