Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is a type of cancer that affects the mouth of cats. It is a malignant tumor that can occur in any part of the mouth, including the tongue, gums, and cheeks. This cancer is relatively rare in cats, but it is a serious condition that can be life-threatening if not treated promptly.

Symptoms of OSCC in cats include bad breath, drooling, difficulty eating and drinking, and weight loss. The tumor may appear as a lump or ulcer in the mouth. Diagnosis of OSCC is typically made through a biopsy, which involves taking a sample of the tumor and examining it under a microscope.

Treatment options for OSCC in cats include surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy. The treatment plan will depend on the size, location, and stage of the tumor. The goal of treatment is to remove the tumor as completely as possible to prevent recurrence.

At the Veterinary Dental Center of Atlanta, our team of veterinarians and dental professionals are well-equipped to diagnose and treat oral squamous cell carcinoma in cats. We use state-of-the-art techniques and equipment to provide the best possible care for your pet.

Tips for catching this invasive neoplasia as early as possible.

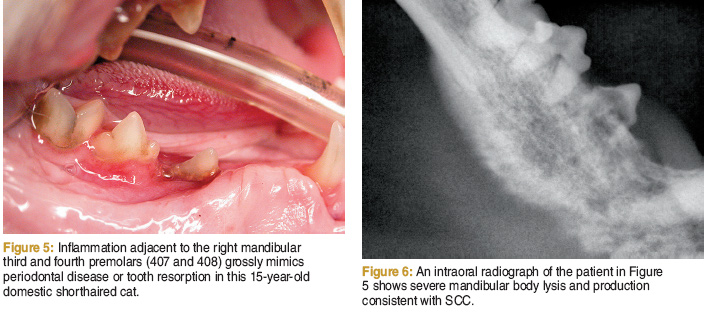

Oral neoplasia in cats requires early detection and brisk therapy to provide any hope of a cure. Locally aggressive with the potential for distant metastasis, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the No. 1 oral neoplasia in cats.¹ Early gross changes may be minimal, and lesions often mimic other feline oral diseases such as tooth resorption and periodontal disease. Radiographic evaluation and examination of deep biopsy samples that include bone, where available, are critical diagnostic tools that differentiate this potentially fatal condition from other oral conditions.

Feline oral SCC carries a generally poor prognosis, with only 50 percent survival beyond one year after diagnosis.² Therapeutically, radiation has proven less than ideal in cats with inoperable SCC,³, but a combination of radiation and chemotherapy is currently being evaluated as a possible option.4; There is evidence that 5-lipoxygenase inhibitors may also play a future role in therapy.5 Further studies in human head and neck SCC may provide clues to potential novel therapies in cats since similarities have identified cats as a potential model for human research.6-8 Recently two cats were treated favorably at the University of Missouri with strontium-90 (Sr-90) radiotherapy.9 But, to date, surgery has provided the most predictable mode of therapy.10

Mandibular SCC

SCC involving the mandible may offer the best option for early surgical intervention, especially rostral and lateral lesions. Surgery is the treatment of choice for cure in select cases. The 3-cm margins achievable in dogs with malignant neoplasia are not feasible in cats with SCC because of small patient size. Margins, however, should be aggressive, and surgical therapy should be left to veterinary dental specialists. Cosmetics and function postoperatively can be very favorable (Figures 1-4).

Maxillary SCC

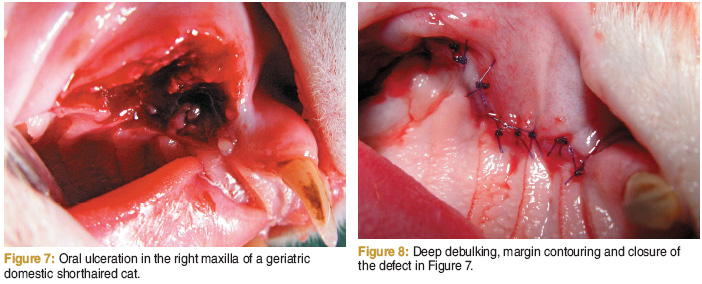

Maxillary SCC is more challenging surgically because of the proximity of vital structures and the need for adequate margins into normal tissue. Gross lesions may appear as gingival inflammation and mimic periodontal disease (Figures 5 and 6). Often, extensive bone and soft tissue destruction is present at this time of diagnosis. In some cases of nonresectable SCC of the maxilla, I have performed debulking to eliminate the oral component of the disease (Figures 7 and 8). A common presentation is proliferation or ulceration adjacent to the maxillary arcade. If removal of painful exuberant oral tissue can result in adequate closure of the defect, patients respond quite favorably clinically. This removes the sensitive tissue from contact with food and normal tongue movements and, in some patients, can provide an excellent quality of life for months before local aggression again reaches a clinical level.

Sublingual SCC

Sublingual SCC often leaves little hope for definitive surgical care. Presentation is generally proliferative or ulcerative (Figure 9). Although generally ineffective, debulking and closure can occasionally be effective at minimizing physical impingement of soft tissue, aiding in mastication and providing comfort. Multimodal pain management is a strong consideration in these patients. Short-term control is all that can be expected, and frequent quality-of-life evaluations should be performed.

Tonsillar SCC

Tonsillar SCC carries the poorest prognosis and the highest potential for distant and early metastasis. Therapy is palliative and consists of pain management and, again, frequent clinical assessments are necessary to ensure quality of life is maintained.

Take-home advice

Although feline SCC is aggressive, excision without recurrence is possible in select cases. If an oral mass is suspected in any cat, dental radiographs and a deep biopsy are needed to confirm. All suspected and confirmed cases should be discussed with the owner, and immediate referral to a veterinary dental specialist should be considered.

Dr. Beckman sees patients in Atlanta and Orlando and teaches extensively, online and live throughout the world

References

1. Withrow SJ, MacEwen EG. Cancer of the gastrointestinal tract. In: Small animal clinical oncology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders, 2001;305.

2. Mantra-Marietta S, Matheissen D, Matus R, et al. Surgical management of oral neoplasia. In: Bojrab MJ, Tholen M, eds. Small animal oral medicine and surgery. Philadelphia, Pa: Lea & Fiber, 1990;108

3. Bregazzi VS, LaRue SM, Powers BE, et al. Response of feline squamous cell carcinoma to palliative radiation therapy. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 2001;42(1):77-79.

4. Fidel J, Lyons J, Tripp C, et al. Treatment of oral squamous cell carcinoma with accelerated radiation therapy and concomitant carboplatin in cats. J Vet Intern Med 2011;25(3):504-510.

5. Wakshlag JJ, Peters-Kennedy J, Bushey JJ, et al. 5-lipoxygenase expression and tepoxalin-induced cell death in squamous cell carcinomas in cats. Am J Vet Res 2011;72(10):1369-1377.

6. Bergkvist GT, Argyle DJ, Pang LY, et al. Studies on the inhibition of feline EGFR in squamous cell carcinoma: enhancement of radiosensitivity and rescue of resistance to small molecule inhibitors. Cancer Biol Ther 2011;11(11):927-937.

7. Martin CK, Dirksen WP, Shu ST, et al. Characterization of bone resorption in novel in vitro and in vivo models of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol 2012 Jan 20. [Epub ahead of print].

8. Tannehill-Gregg SH, Levine AL, Rosol TJ. Feline head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: a natural model for the human disease and development of a mouse model. Vet Comp Oncol 2006;4(2):84-97.

9. Nagata K, Selting KA, Cook CR, et al. 90Sr therapy for oral squamous cell carcinoma in two cats. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 2011;52(1):114-117.

10. Northrup NC, Selting KA, Rassnick KM, et al. Outcomes of cats with oral tumors treated with mandibulectomy: 42 cases. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2006;42(5):350-360.